Tri-City Herald, Sunday, January 2, 2005

Yakamas First at New Museum

©2005 Valerie Kreutzer

The Yakama Nation was the first community asked to participate in exhibits at the new National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C. The Yakama are also the only group from the Pacific Northwest representing contemporary Indian life in the museum’s current exhibits.

The Yakama Nation was the first community asked to participate in exhibits at the new National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C. The Yakama are also the only group from the Pacific Northwest representing contemporary Indian life in the museum’s current exhibits.

“How do you live your identity, we asked the tribal leaders,” recalls Taryn Constanzo, a Smithsonian researcher who visited Eastern Washington’s plateau region often and participated in her first potlatch there.

With assistance from Constanzo, Yakama elders became curators of their own show. Over a three-year period they discussed everything from community struggles to tribal legends, always mindful not to disclose everything about their culture and spirit. They also donned hardhats when they visited the museum’s construction site to help the Smithsonian conceptualize this museum as a Native place.

“We try to continue our traditions, including language, the longhouse, the sweathouse, and caring for the environment,” Yakama curators write. “At the same time, we recognize that 21st-century life has created distractions that infringe on traditional responsibilities. Our challenge is to find a balance between the two.”

Life in the balance defines the Yakama’s circular exhibit that is dominated by an image of mighty snow-capped Pahto (accent over a), Mt. Adams.

Finding a balance isn’t easy, writes Marilyn Skahan-Malatare: “My daughter’s got a moccasin on one foot and a tennis shoe on the other. She’s trying to balance them out—and at 16 years old she’s having a pretty hard time.”

E. Arlen Washines, Yakama Nation wildlife manager, observes: “At one time people on our reservation had to take time off from doing traditional things to go to school or work. Now our traditional way of life is part-time and we only do it during feasts or on the weekend.”

Photos, texts and videos give insight into history and life on the 1.2-million-acre reservation that is guaranteed by the 1855 treaty with the U.S. government. “We were never put on a train and taken away. We were fortunate that we never went through a Trail of Tears,” explains an elder.

The treaty is celebrated every year during a three-day festival that includes a rodeo, a parade and the Miss Yakama pageant. Miss Yakama’s beaded crown sits in a display case. “We asked them to make a duplicate for this show,” explains the Smithsonian’s Constanzo. She points to wapaas, berry baskets, in another display. Next to ancient woven grass containers on belts sits a Folger’s coffee can on a string, a modern gadget for old traditions.

“There are 10 different huckleberries,” explains a young woman in a video. “The berries are sacred. You have to pick them with a clean mind. If you don’t have clean thoughts, they become unclean.” A good heart and a clean mind are also necessary in the preparation of a potlatch, insist two older women: “Bad thoughts spoil foods. If we don’t cherish our foods, the creator will take them away from us.”

Visitors to the exhibit nod in agreement. But not all are pleased.

“Where are the Navajos, the largest Indian group in the U.S.,” demands a visitor.

“They’ll get their turn,” promises a researcher in the museum’s Resource Center. “There isn’t enough room for everybody at the same time. These are evolving exhibits.”

The museum is a work in progress. At its core is a collection of 800,000 objects that include baskets, tools, weapons, totems and masks. These works of cultural and spiritual heritage span more than 10,000 years. The showcases are surrounded by exhibits that tell the story of native peoples past and present, but in a novel way. Instead of letting the “experts” tell it, Smithsonian curators asked the tribes to define and present themselves.

That’s a radical departure from the usual show-and-tell, Smithsonian curators point out in one of their video presentations. Indians were first “discovered” by European explorers; they were portrayed and photographed by white men; they were depicted in Hollywood movies, and vilified and romanticized in Western novels. At the NMAI, finally, Indians speak for themselves.

Established through an act of Congress in 1989, the structure fills the last remaining spot on the Mall and is the closest museum to the U.S. Capitol up on the hill. At the request of many tribes, the museum’s entrance faces east to the rising sun and is aligned with the Capitol’s dome as if in a gesture of vindication.

Its grand opening on September 21 of this year drew a multitude of Native people in festive attire for the largest parade ever on the Mall. It almost made the builders of the NMAI forget that the road towards its completion was anything but smooth.

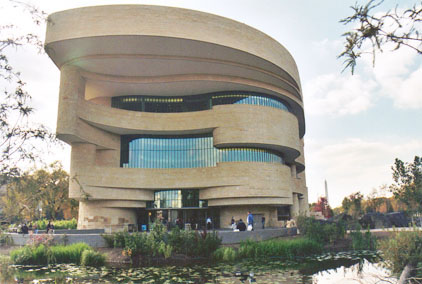

There’s the controversy over the museum’s spectacular design. Its Indian architect from Canada, Douglas Cardinal, and his U.S. collaborators were fired by the Smithsonian in 1998. Others had to bring the project to completion, but Cardinal’s signature masonry curves live on. If you’ve ever seen his Canadian Museum of Civilization across the river from Canada’s Parliament Hill in Ottawa, you recognize the Cardinal trademark elements of worn-looking limestone assembled in organic-flowing swirls.

At the museum’s opening Director W. Richard West, a Southern Cheyenne, said that the Smithsonian Institution is “forever indebted to Douglas Cardinal for his work of genius.”

Cardinal, a Blackfoot, was invited to the opening but refused to attend. His design, said Cardinal, “was not a gift but professional work for which I should be reimbursed.” The Smithsonian insists that Cardinal was properly compensated when the relationship was terminated.

You can read the letter exchange between Cardinal and West on the architect’s Web site, www.djcarchitect.com. In his conciliatory note West writes: “Your design for the National Museum of the American Indian’s National Mall building will be a principal physical and, indeed, spiritual marker for the Native peoples of this hemisphere long beyond the lives of either of us.”

The critics agree. The Washington Post’s Benjamin Forgey calls the building a “natural wonder that channels the spirit of the earth.

“Those dramatic cantilevered bands above the entrance are scintillating when seen from afar, like some natural wonder you might see in New Mexico,” writes Forgey. “And when you stand far beneath the cantilevers in the museum’s circular forecourt, the scale has an almost physical effect. You feel both overwhelmed and sheltered. I can’t think of another architectural space quite like it.”

The grounds surrounding the museum feature wetlands, waterfalls, traditional crops and plants indigenous to the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River areas. Forty granite boulders—called Grandfather Rocks—welcome visitors at the entrance and are reminders of the Native Americans’ long relationship to the environment.

“When we come to this museum we want to see something of ourselves,” said an Inuit woman on a visit. Thousands come every day looking for connections. A young woman we spotted outside the Lelawi Theater seemed to have found hers. She had just watched a 13-minute multimedia presentation on indigenous worldviews and celebrations of the natural world.

“And there was grandpa in all of his regalia,” she reported excitedly to someone over her cell phone. “Imagine, grandpa…”